Early PC games were packed with great soundtracks and technological developments, but the real advances were still to come. With sound cards and CD-ROMs becoming more mainstream the technical and artistic horizons of composers broadened considerably. Soon full orchestral scores would be the norm, but before then, technology was still catching up. The 90s then, were a period of transition bridging the MIDI age with what we know today.

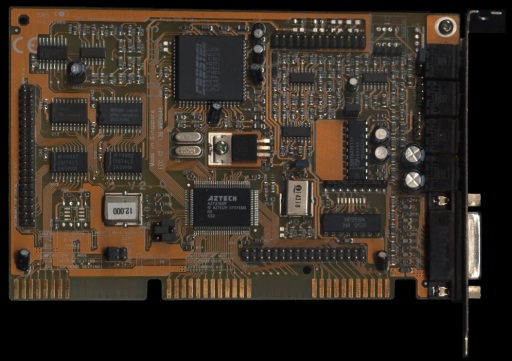

Yes, that’s a joystick port on the end. Ah, the pre-USB days…

Last time we saw how MIDI revolutionised game soundtracks and kick-started an era of technical advances and artistic expression that would set video game music on the path towards the fidelity and cinematic immersion we take for granted today.

Creative and AdLib were the big players in mainstream sound card – AdLib went bankrupt in 1994 while Creative are still releasing audio hardware today. My first graphics card was an Aztech model, “compatible” with AdLib and Creative cards. I put quotes around compatible because actually getting audio to work in many cases was a dark art involving blood sacrifice and forbidden rites. The sound card arrived at the same time as my first CD-ROM drive which had the very latest “multispin” technology – meaning “twice as fast”. A 2x drive, basically, though at the time it was impressive enough to warrant a name all of its own. Today, of course, CD-ROM drives topped out at 72x and can write at 56x. As if anyone owns an actual CD-ROM instead of DVD or Blu-ray drive…

That single upgrade did more to change my gaming experience than anything else I’d done before or since. Someone who missed out on the early days of DIY PC upgrades simply won’t understand the joy that came from putting in a new CPU or upgrading the RAM. Of course these things still happen but the impact just isn’t as great. A better video card might mean using 8X anti-aliasing instead of 6X, or getting slightly better shadows. The jump from a 386-66 to a 486-100 was simply incomparable. Everything changed, and the feeling you got as a child or a young adult (presumably as an older adult too) when you first loaded a game on the new hardware is indescribable. This will have to do:

Some kind of celestial event. No – no words. No words to describe it. Poetry! They should have sent a poet. So beautiful. So beautiful… I had no idea.

– Dr. Ellie Arroway, Contact

So let’s crack on…

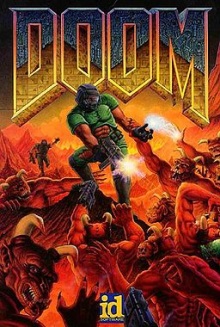

Doom

The seminal masterpiece of id Software which catapulted John Carmack and John Carmack to the status of computer game legends was released in 1993, just in time to make my new sound card cackle in glee. The game surely needs no introduction or analysis, but the music and the technology driving it are worthy of note.

The seminal masterpiece of id Software which catapulted John Carmack and John Carmack to the status of computer game legends was released in 1993, just in time to make my new sound card cackle in glee. The game surely needs no introduction or analysis, but the music and the technology driving it are worthy of note.

Not Even Doom Music

Go and watch the Errant Signal discussion of Doom. Go on, I’ll wait. Right, good. As he says, the music in Doom – like so much of the game – came purely from what the developers knew and liked. That level of personal direction could so easily have made the game a flop if their own tastes hadn’t connected so well with the generation of gamers they were engaging with, but as it was the game, the style, the mechanics, the tone and the music all fit perfectly. At first glance, Doom cries out for a tense, low, atmospheric music to emphasise the horror and the fear. The pacey heavy metal score written by Bobby Prince shouldn’t fit, and yet it works so very well.

MUSic

The music in Doom is essentially a clone of the MIDI standard. From a description of the format:

A .MUS file is a simple clone of .MID file. It uses the same instruments, similar commands and the same principle: a list of sound events.

– MUS File Format

It was designed by John Carmack to be more compact than MIDI, a necessity given how asset-rich Doom was for the time. The game shipped on four floppy disks and keeping things small and manageable was critical. MUS files were limited to 64KB in size and used only 9 MIDI channels – 8 for melody instruments and the 9th for drums. This was purely a compatibility concern – many older soundcards has FM sound chips with only 9 FM channels so that was the level the developers targeted.

By keeping as close to recognised standards as possible for game assets Doom was one of the first games to spawn a broad and fanatical modding community, with efforts ranging from texture packs, new levels, new weapons, new sound packs and even total conversions. The music was no exception and as MUS was so similar to MIDI it was trivial to convert from one to the other. It wasn’t always a perfect conversion, but more than enough to facilitate easy composition for the game and its mods.

Eventually MIDI style music and its derivatives would be replaced by the audio formats we know today, but bandwidth, processing power and storage capacity would hold that back for a while yet. In the meantime, the CD was doing something remarkable.

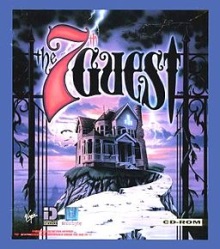

The 7th Guest

Released in 1993, this was one of the first ever games to be released exclusively on the CD-ROM – there was no practical way to make it fit on floppy disks without removing everything that made the game special. As such The 7th Guest is credited as being a killer app that helped accelerate the adoption of the CD-ROM in the mainstream and cementing its place as a cornerstone of modern gaming technology.

Released in 1993, this was one of the first ever games to be released exclusively on the CD-ROM – there was no practical way to make it fit on floppy disks without removing everything that made the game special. As such The 7th Guest is credited as being a killer app that helped accelerate the adoption of the CD-ROM in the mainstream and cementing its place as a cornerstone of modern gaming technology.

So take the time / To find out what’s inside

The 7th Guest was one of a handful of games that might be described as an “interactive movie”. Later, on a whopping four discs and notably starring the lovely Tia Carrera, The Daedalus Encounter would go even further down that road, and then two years later Blade Runner would do the same.

The 7th Guest was one of a handful of games that might be described as an “interactive movie”. Later, on a whopping four discs and notably starring the lovely Tia Carrera, The Daedalus Encounter would go even further down that road, and then two years later Blade Runner would do the same.

Due to the nature of the game at any given point it was doing very little but playing music and video. This left the game free to make use of unprecedented amounts of video and pre-recorded audio rather than MIDI or older technologies. The result was a truly memorable experience – the plot may have been simple, the characters shallow, the acting poor and the puzzles either laughably simple or keyboard-snappingly hard but the experience was one of sound and video. People still remember it today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tLP6gqaXRJw

The music was composed by George “The Fat Man” Sanger who was already a leading name in video game composition – Wing Commander, Loom and the NES edition of Maniac Mansion, among others. The game shipped with a second CD containing a single audio track comprising the game’s music and two live recordings – “The Game”, which formed the core of the theme to The 7th Guest, and the jazzy “Skeletons in My Closet” from the end credits.

Despite being a somewhat mediocre game and something of a genre dead-end, unencumbered by space or performance constraints The 7th Guest nevertheless broke new ground in what would be possible on the PC in years to come. It might be some time before CD quality music could be integrated into, say, an action game, but Trilobyte took those first steps along the road and the industry eagerly followed.

That was 1993. Jump forward five years and watch Epic MegaGames make the next generational leap in gaming technology.

Unreal

After Doom and Doom 2, id Software took the gaming world by storm with Quake in 1996 and almost single-handedly redefined 3D gaming, multiplayer, competitive gaming and speed-running. But I wasn’t a Quake boy. No sir. In 1998 I found Unreal. And it was beautiful.

After Doom and Doom 2, id Software took the gaming world by storm with Quake in 1996 and almost single-handedly redefined 3D gaming, multiplayer, competitive gaming and speed-running. But I wasn’t a Quake boy. No sir. In 1998 I found Unreal. And it was beautiful.

The cramped and claustrophobic opening level aboard the Vortex Rikers hints at a horror game, but then the level ends and you emerge outside into a sprawling brightly lit alien world that looked like nothing else that gaming had shown before. It was a solid kick in the teeth to Quake’s oft-derided browns, and in those first two levels I knew I was seeing the next era of gaming unfolding before me.

The Unreal Engine made use of two notable audio technologies, one new and one a decade old.

Environmentally Friendly

Unreal was the first game to make use of EAX (Environmental Audio Extensions, a suite of digital signal processing presets used by Sound Blaster cards. By offloading the work to dedicated hardware EAX allowed sound effects to be modified to fit the environment. In an enclosed space sounds would become sharper with a local reverb, while in an open area sounds might echo off distant cliffs.

This greatly enhanced the ambience and hugely increased the degree of immersion by creating a more perceptible link between the gameplay area and the audio. Not being music-related, EAX is here purely as an honourable mention – it really was a marvel to hear in action and genuinely contributed to Unreal’s success as a evolutionary leap in gaming.

The Hand of MOD

Where EAX was a new technology, fresh out of the labs, the music used a technology with a much longer heritage. With such an intense, processor-, memory- and graphics-hungry game, CD quality music wasn’t going to be possible. Therefore the Unreal Engine used module music. This was long-established from the Amiga days and was popular in the Demoscene culture.

As with MIDI, MOD files are essentially descriptions of music rather than recordings. The difference, and it is a crucial difference, is that the MOD files contain their own samples rather than relying on the playback hardware to provide their own. This increased the size of the music significantly, but computers were more powerful now and disk space was fast becoming vanishingly cheap. Using MOD files games could have music that was far richer than MIDI and guaranteed to sound the same regardless of the playback device (largely, although some of the effects which could be applied might vary from system to system), all at the expense of a little disk space and a few more cycles of processing power.

As with MIDI music MOD tracks are amenable to realtime, iMUSE-esque modification allowing for mood changes and immersive scoring.

The soundtrack to Unreal was written primarily by Michiel van den Bos and Alexander Brandon (more from them later…), with contributions from Dan Gardopée and the wonderfully-named Andrew Sega.

[Full playlist]

As you can hear, MOD allows for a very rich soundtrack, and the variety in tone is impressive. Compare and contrast the gentle “All Hallows Sunset” with the electric “Isotoxin”, or the sweeping “Flight Castle” with the discordant “Erosion”.

In interview, Alexander Brandon had this to say about working on the Unreal soundtrack:

Unreal was a very different kettle of fish. The scope was huge, the expectation was huge, so we got more feedback from both Cliff and the other designers. At the beginning, oddly enough, it was Cliff and Tim who pushed making the music interactive. I was a young stupid kid at the time so I didn’t know any better, but in the end it was a great idea and a lot of fun to see working, plus it helped the experience become more dynamic. For the most part music just got delivered and level designers plopped in the pieces.

In the same interview he confirms something I suspected from the word go:

With Unreal, though I harp on gameplay, the visuals were the first inspiration. They created the tone of the music and the selection of instruments. But the behavior was determined by gameplay.

And finally, an insightful snippet on the two – sometimes conflicting – ways in which music is driven during a game:

For more story driven games music presents a far more emotional experience. Drake’s Fortune, Bioshock, and many others that have a strong story component that you can’t just ignore will have music as a vital component of how things are scripted. At the same time, it’s hard to ignore that those moments are written before you have anything to do with them, for the most part. Other titles such as Sworcery (iOS game) present unique game play interactions and unique ways of using audio and music to respond to them. The same goes for Braid, and other games that use new interaction mechanics.

For a story- or narrative-driven game the music has to respond to and underpin the story, but other times the music has to respond to events created and situations created by the player, and the music may be incredibly tightly coupled with the gameplay. Each poses unique challenges, especially when they may both occur in the same game.

Unreal pulled that off with flair, with the music moving smoothly from ambient exploration to tension to combat and back again, while at the same time following cues on precisely-directed set pieces.

Michiel van den Bos has this to say about writing for Unreal:

We knew what the projects were, we got some ideas as to what the maps looked like and just made music for them. They weren’t easy gigs ‘creatively’ due to the severe limitations of Impulse Tracker (the program I used to score these games) and getting such a big sound out of that small program wasn’t straightforward. I didn’t have the hardware to the beta stuff they sent, so the designers basically wrote e-mails outlining what the maps would look like and what kind of atmosphere they were going for.

Which makes the outstanding results all the more impressive and goes to show what you can achieve when the goal is to create music to support the environment and the atmosphere. It’s also interesting to learn that even with a well-established format, late in the 90s and with the state of the art at the time that composers were still having trouble with their supporting tools and software.

Two years later, Alexander and Michiel return with the soundtrack to probably the best game ever made.

Deus Ex

Again, I’m not going to go into what makes Deus Ex so great a game – fully half of the internet is devoted to just that. Argh! OK. Just one thing. Believable characters with real, understandable motivations! You! Other game designers! Is that so difficult to understand? Phew. Moving on.

Again, I’m not going to go into what makes Deus Ex so great a game – fully half of the internet is devoted to just that. Argh! OK. Just one thing. Believable characters with real, understandable motivations! You! Other game designers! Is that so difficult to understand? Phew. Moving on.

In keeping with the game being heavily story and character based, but at the same time being open, non-linear and player-driven, the music features an iMUSE style dynamic system which allows the music to switch seamlessly between variations on a theme to alter the music based on what the player was doing and what was happening around them.

From an interview with Big Giant Circles (and isn’t that just magical in itself?):

Unreal was very much a situation where I just wrote music and it magically went in. I haven’t been that lucky since but Deus Ex followed that tradition, except that I had a very good idea of where the locales were beforehand … It’s really up to the composer to push themselves into the process, and do it intelligently depending on what the design of the game might or might not call for. It’s also up to producers to be able to respond to this openly, at least up to a point where budget and schedule permit.

And in an interview with DeusEx Machina:

The team members definitely have individual ideas about what music they see… level designers are usually my more constant feedback supply because they’re attached more closely to individual levels, and the lead designer will give overall approval based on his vision as well.

Deus Ex remains an outstanding game and spawned a truly worthy prequel. But does the soundtrack measure up to Human Revolution’s?

[Full playlist]

Yes, obviously. Sharing composers, engine and format, the music is immediately recognisable as sharing a heritage with Unreal, but very quickly goes in its own direction with a series of timeless tracks – UNATCO, The Synapse, DuClare Chateaux… And then to top it all off, Conspiravision, a direct remix of the Nightvision track from Unreal. I am ashamed to say, I never put two and two together before.

And just to make things even better, Alexander Brandon teamed up with OC Remix to produce a remix of the Deus Ex soundtrack called “Sonic Augmentation“, just in case you were already getting withdrawal symptoms.

More of that sort of thing please world.

Trackers

![]() Tracking software has been mentioned several times now, so it worth taking a quick look at what they are, where they came from, what they do and where they’re going.

Tracking software has been mentioned several times now, so it worth taking a quick look at what they are, where they came from, what they do and where they’re going.

A tracker is a type of music sequencer which is used to create MOD files. The composer can assign a sample to a channel and from that sample specify a sequence of notes (pitch-shifted variations on the sample) along a timeline. A sequences of notes, effects (vibrato, arpeggio, etc.), parameters and commands form a pattern and a set of patterns forms the completed song.

The first tracker was Ultimate Soundtracker, which was written by Karsten Obarski for the Amiga in the late 80s and gave its name to the family of software which was to follow. Despite being buggy and difficult to use it soon became a standard for the Amiga. it did not enjoy commercial success, but after the source code was released into the public domain clones and improvements spread across the Amiga underground.

When Creative lines of sound cards started to gain traction and PC audio approached CD quality tracker musicians drifted to the PC. As PCs became more powerful the necessity for dedicated hardware to perform audio mixing and processing diminished and soon mainstream CPUs were more than equal to the task. With more power came increased capacity and the number of channels grew from 4 to 8 to 16 to 32 and eventually to 64 with Impulse Tracker. Nowadays there is no effective limit on the number of channels as computers can trivially mix huge numbers of channels together in real time.

Tracker software is still in use and under development though it is increasingly a niche occupied by hobbyists and specialists. Innovation continues, however – for example, in 2011 a tracker called Sonant Live was released as the world’s first browser-based tracker.

Just for fun and to take a quick refreshing break from soundtracks for a moment, here’s some more examples of MOD music created with trackers:

IndusTree's Homesick (Ogg)

Pale Dreams - included with an early release of Impulse Tracker (Ogg)

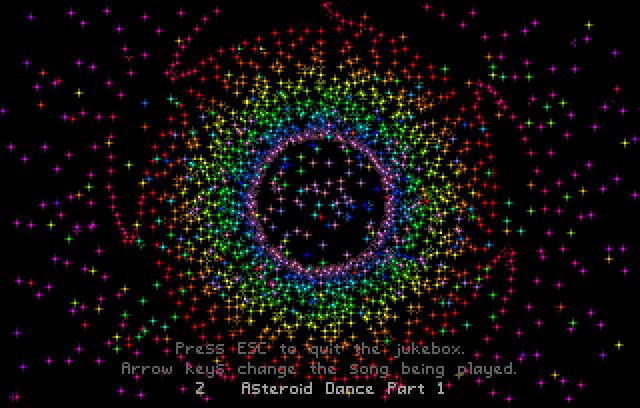

Honourable Mention: Tyrian

Since this seems to be Alexander Brandon Week, it would be remiss of me not to mention Tyrian, the superb vertically scrolling shmup released by Epic MegaGames in 1995. It featured music composed by Alexander Brandon, with additional tracks by Andreas Molnar. The music was made using the “Loudness” Sound System developed by Andreas in 1993, a tracker program intended to be an easier way to create music for the AdLib sound card. Tyrian was justifiably proud of its soundtrack, and was one of the first – if not the first – games to include a jukebox in the menu so players could browse the soundtrack at leisure. Not only that, but the developers added a visualiser to go with it, something so pointlessly cool that seemed to come direct from the demo scene.

Since this seems to be Alexander Brandon Week, it would be remiss of me not to mention Tyrian, the superb vertically scrolling shmup released by Epic MegaGames in 1995. It featured music composed by Alexander Brandon, with additional tracks by Andreas Molnar. The music was made using the “Loudness” Sound System developed by Andreas in 1993, a tracker program intended to be an easier way to create music for the AdLib sound card. Tyrian was justifiably proud of its soundtrack, and was one of the first – if not the first – games to include a jukebox in the menu so players could browse the soundtrack at leisure. Not only that, but the developers added a visualiser to go with it, something so pointlessly cool that seemed to come direct from the demo scene.

Hours of my life. Hours I say.

The Times Ahead

The mid to late 90s might be my favourite time for video game music. Every era had its charm, its standout tracks, albums and games and it would be foolish to claim that any period was objectively better than any another. But from now on, the music becomes high-fidelity, studio recorded, orchestral, choral, real. When you get people like Hans Zimmer scoring video games, they aren’t video game soundtracks any more. They’re soundtracks. They’re not worse for it, in fact they’re often amazing and superlative scores are being produced every year, but the time when the music was unique to the world of video games is long since past. To me Deus Ex was the last time a video game soundtrack truly justified the qualifier.

As sorry as I am to bid farewell to MODs, they’re dead.

– Alexander Brandon