In honour of the fact that we will soon be ruled by machines it’s maybe worth taking a look at how the video games industry is helping to bring about our doom. Or not, in some cases.

Bethesda have never lacked for ambition when it comes to populating their massive game worlds with NPCs, and the Elder Scrolls games are stuffed full of people that – by and large – get on with their days making a fair attempt at simulating a believable world that existed before the player arrived and will continue to exist after she leaves. But that verisimilitude is only paper-thin. Look too close, or poke too hard and the whole thing turns into a farce. Just see the whole Bucket Head Theft business if you don’t believe me. On the one hand, yay for emergent behaviour! On the other hand, doh!

The illusion is broken and he seems even dumber than the NPC who never did anything and had no personality.

Over at Twenty Sided, Shamus Young takes a closer look at the problem, using the theft system as a case study for the Skyrim AI system as a whole. He likens the problem to the uncanny valley – the more “real” the AI gets the stranger it seems to us. I’d never made that particular connection before but it’s extremely insightful. I wonder what kind of breakthroughs we’re going to have to see in AI before Elder Scrolls IX actually lives up to Bethesda’s dreams?

I can’t dance with Elizabeth. But I could shoot the civilians around her.

It’s a shame that Bioshock Infinite was such an awful game because by all accounts Elizabeth, the AI companion you pick up later on is an absolute treasure. Over at Kotaku Patricia Hernandez had a similar reaction to me but she was able to keep playing and found that Elizabeth actually seemed more human, more real, simply through contrast to the player. By showing Elizabeth doing simple things, human things, things denied the player, she automatically seems more human by comparison. I don’t know if this was intentional but it was certainly effective.

We knew right away we wanted her movements and her face to be somewhat exaggerated because quite often you observe her at a distance

Eurogamer’s Wesley Yin-Poole did an interview with Irrational’s Ken Levine who talked about the challenges of creating a single believable AI companion for the player. Unlike Skyrim where the developers were trying to create a broad system for a whole world Irrational needed to make one character who would be with the player at all times. That meant she had to be consistent, believable, unobtrusive and absolutely not annoying. A much different challenge to that facing Bethesda but barring some extremely elegant breakthrough in behavioural programming it possibly indicates the level of complexity every single NPC would need to achieve their vision. Just as even minor background characters now have polygon counts in the thousands, might even Eric the beggar need an Elizabeth-level AI to keep him feeling like a real person?

The player is actually an NPC to us, so the AI system can interact with the player or can use the player as an NPC.

Following a wildly successful Kickstarter campaign Warhorse are working on Kingdom Come: Deliverance. What we’re hearing from the developers are hitting all the right notes – “at no point will you have to collect seven pieces of a legendary magic staff” – and they seem to be taking a Skyrim-plus approach to AI and world-building. It will be interesting to see how well they manage to pull it off. It sounds that they’re going for a contained set of rules and relatively simple interactions which should hopefully come together in a self-consistent system that holds up better to scrutiny and player-interference than recent Elder Scrolls games.

Even with path smoothing and all that, you still get these less than human looking movement patterns that always bothered me.

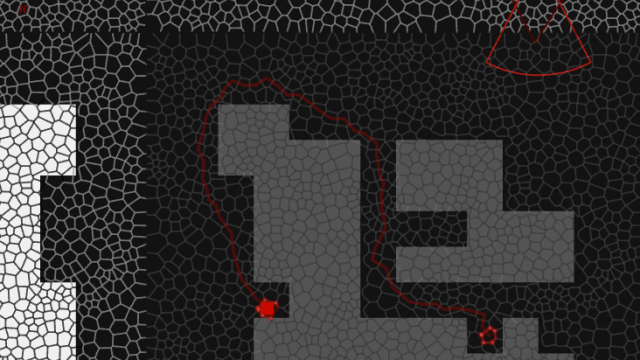

Stepping away from the big picture for a moment, let’s focus on one particular problem in AI – path planning. I’ve touched on this before when I linked to Matt Klingensmith’s Overview of Motion Planning, and now we turn to Sven Bergstrom’s Pathing excursions: More Natural Paths where he describes using Voronoi diagrams to feed an A-Star algorithm. What he comes up with is indeed a much more natural-looking path than you might get from a pure grid-based system. Of course it suffers from the expensive up-front network generation – even more so since you have to tweak the algorithm to get the “style” you want for a given map; this likewise makes it difficult to have maps be dynamic or be updated in real-time. Still, it’s an interesting system and I’ll never pass up a chance to use the phrase Voronoi diagram.

Instead of trying to solve a massive problem in one feel swoop, I taught the AI to solve very simple problems and then layered these solutions to create more and more complex behaviors.

Let’s turn once again to Gamasutra and finish up with something a better writer might have started with – David Paris’s article Gameplay Programming Hints: Building AI which offers a nicely accessible high-level overview of how to design an AI system. He takes as his basis a typical military system, but only because it lends itself nicely to a simple hierarchy that makes for an easily understood example. Then he uses that hierarchy to separate out layers of complexity and abstraction into discrete systems that handle their own elements of the overall goals. This allows for a massive degree of flexibility and ability to respond to rapidly changing conditions or unexpected new information. The overall goal (get to the checkpoint) can stay the same while the low-level decisions can shift wildly (forget keeping low and quiet, toss grenades and run for it).

This is also how many strategy games work. In his dev blog for Enemy At The Gates, Jon Shafer goes into great depth on how he plans to use just such a system to control the AI factions. Well worth a read.

Well there you have it. More AI than you can shake a Voight-Kampff machine at. Hopefully you learnt something from it all.